Monetary Policy

The following headlines have been reprinted from The Penn Wealth Report and are protected under copyright. Members can access the full stories by selecting the respective issue link. Once logged in, you will have access to all subsequent articles.

Keep track of the Fed's balance sheet by clicking here.

Keep track of the US national debt by clicking here.

|

FFTR

3.0-3.25% 23 Sep 2022 |

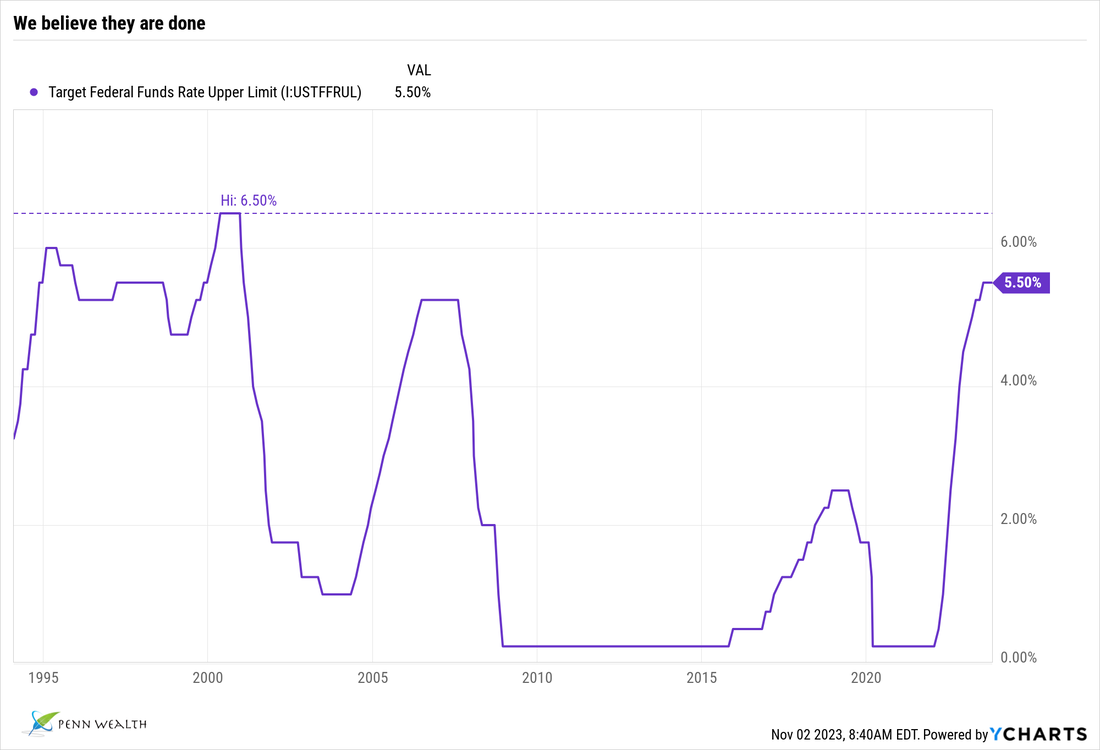

Powell’s words left little doubt: rate hikes until inflation is under control

For anyone who still believes the stock market is rational and efficient, consider this: Going into the Fed’s rate decision, the Dow was trading up a few hundred points; within seconds of the fully-expected 75-basis-point rate hike, the Dow was down a few hundred points; during Powell’s post-decision speech, the Dow rallied into the green by several hundred points, only to close the session down 522 points. No matter how late investors or pundits may believe Powell was to the party, his message has been crystal clear: Rates will go up until inflation is brought down to acceptable levels. While the official “acceptable” level is 2%, he said something very telling in his news conference: “The ultimate goal is to have positive real rates across the yield curve.” To us, that was meaningful. By “real rates” he means inflation adjusted, so if the 2-year Treasury is yielding 4% then inflation must be below that. They say markets don’t like uncertainty; well, we now have full clarity with respect to what the Fed plans on doing next. Of course, we still don’t know how many rate hikes and other shocks to the system it will take to tame inflation. Furthermore, it will take time for the hikes to have their full effect on economic conditions as Fed actions typically have a lot of lag. The central bank forecasts a funds rate of 4.4% by the end of the year, which would point to one more 75-bps hike in November (there is no October meeting) plus a 50-bps hike in December. From there, we may see a few quarter-point hikes before the Fed pauses. We thought it would take a lot to get the fed funds rate to 4%; odds are now in favor of a 5% terminal point. That’s high, but not disastrous for the economy. For historical perspective, we were sitting at a 6.5% rate in August of 2000 and a 5.25% rate in May of 2008. Despite the market tantrums, the economy will weather these rates just fine. A combination of two catalysts will fuel the coming market rally: signs that inflation is finally coming down, and the Fed’s indication that a pause in hikes is near. We see both of these indicators appearing within the next four months. In the meantime, own quality equities and load up on fat-yielding, shorter-maturity bonds. |

|

FFTR

2-25-2.5% 29 Jul 2022 |

Powell’s Volcker moment: Fed proves it is serious about reining in inflation

They were the largest back-to-back rate hikes since the early 1980s, when Paul Volcker rode to the rescue of the American economy by raising rates until runaway inflation was defeated. Current Fed Chair Jerome Powell acted—and sounded—a lot like his predecessor of forty years ago this past Wednesday. And investors liked what they heard, sending stocks soaring (the Nasdaq rose 4.06% in one session). The 75-basis-point rate hike took the upper limit of the Fed funds rate to 2.5%, and odds are we will see another three hikes by the end of the year. Let’s assume they manifest as one 50- and two 25-basis point hikes; that would bring the rate up to 3.5% going into 2023. We would like to see an ultimate terminal point of 4%, but considering the economic slowdown, that may be wishful thinking. Ironically, the market rallied after the big mid-week hike based on more dovish expectations going forward. While Powell certainly didn’t signal that rate cuts might be on the table next year, that is what investors have read into it. Many believe that the tightening cycle will end in 2022, with rates easing back down in 2023. We hope they are wrong. A strong economy can coexist with more normalized rates; rates that allow investors to earn a decent return on their fixed-income portfolio. That is the sweet spot we should be looking for—not a return to zero interest rates. Unemployment has been the missing piece in the recession narrative, and a good excuse for the Fed to keep hiking. Based on what companies have been telegraphing, that will soon change. As the unemployment rate begins heading up from its current level of 3.6%, we can also expect the widespread unionization efforts to begin fizzling out. No comments on that point. |

|

Fed Balance

Sheet $8.91T |

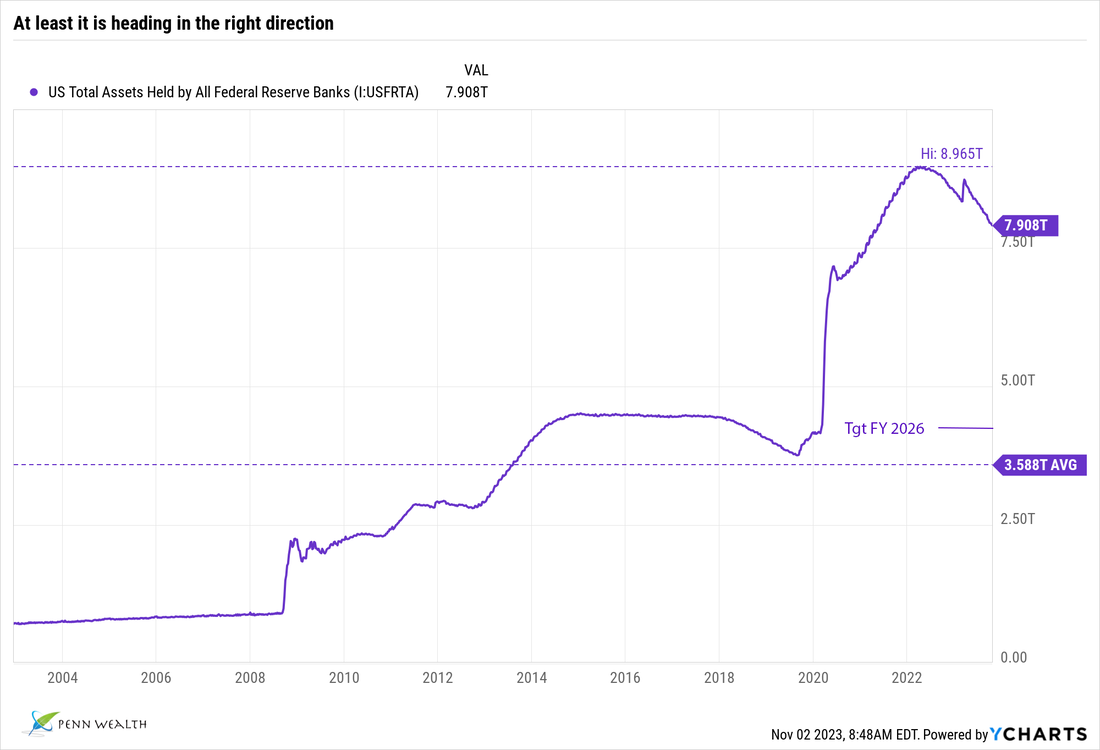

The Fed will finally start reducing its $9 trillion balance sheet this month

(01 Jun 2022) It is hard to imagine, but just nineteen years ago, in 2003, the Federal Reserve had around $700 billion of assets on its balance sheet. That amount, it should be noted, is one component of the national debt. After the financial crisis of 2008-09, the balance sheet more than tripled, hitting $2.25 trillion. At the time, those figures were hard to fathom. Quadruple that amount and we have the current size of the Fed balance sheet. June is the month the figure finally begins going down. Four large Treasury securities held by the Fed, worth $48.25 billion, are maturing this month. In previous months, the Fed would have reinvested the proceeds, purchasing an equal amount of new securities. Instead, it will let $47.5 billion simply run off the balance sheet, only reinvesting the final $1 billion or so. It will continue this process until September, at which time it will double the amount allowed to mature without reinvestment, reducing the balance sheet by $95 billion per month. This may seem like a rapid pace, but it will only amount to a $522 billion reduction by the end of this year, and an additional $1.1 trillion by the end of 2023. If the downward trajectory continues, the Fed balance sheet will be back to pre-pandemic levels by the summer of 2026. That date may seem far in the future, but there is something even more unsettling about the entire process: we will probably never get there. The continued reduction is contingent upon the economy humming along between now and June of 2026. Does anyone really believe that yet another “urgent crisis” will fail to manifest? Our best hope is that the balance sheet is reduced by a few trillion dollars before the Fed is forced to go on its next buying spree. Rarely are two of the Fed’s three main tools used in tandem, at least to this degree: an increase in short-term rates plus a simultaneous reduction of the balance sheet through open market operations. These two actions will undoubtedly have an impact on the housing market specifically, and the overall economy in general. Hence, the doubt expressed by economists that the Fed can execute a “soft landing” as opposed to fomenting a recession. A fascinating case study to watch. |

|

FFTR

0.75-1% |

Fed raises rates most in one meeting since May of 2000; let’s hope the trend continues

(05 May 2022) In May of 1999, twenty-three years ago this month, the upper limit of the federal funds rate (FFR) was sitting at 4.75%. In an effort to prevent runaway inflation and cool the scorching-hot US economy, the Fed began raising interest rates. It capped that effort one year later, in May of 2000, when it raised rates 50 basis points, from 6% to 6.5%. Why is that history lesson important? Because, to staunch already-runaway inflation, the Fed just made its biggest move since that meeting twenty-two years ago: the Committee spiked rates (upper limit) from 0.50% to 1%. The history lesson also brings home another point. When rates topped out at 6.5%, the central bank had an enormous amount of room to tighten as it worked to avoid recession, which it did (lowering rates) between 2001 and 2003. The accompanying graph provides a wonderful visual for the difference between then and now. Rates must continue to go higher. At the very least, we need to get back to the average FFR of 2.5%. To do so in a timely manner would entail another 50 basis point hike at both the June and July meetings, respectively, and a 25 basis point hike in both September and November. Unless inflation shows real signs of cooling, that is the scenario we can expect to play out. We can also expect a few hikes in 2023, bringing the FFR up to 3% or higher. In addition to the hike, Fed Chair Jerome Powell also announced a systematic paring back of the Fed balance sheet, which remains just shy of $9 trillion. More perspective: that debt load sat well below $1 trillion back in 2000. Starting in June, that astronomical figure will be reduced by $95 billion per month, equaling a $1.1 trillion reduction by May of 2023. Again, a good start. With any luck at all, inflation can be tamed without the rate hikes pulling us into a recession until 2024—though the latter scenario may well play out in 2023. The longer we can keep a recession at bay, the more ammo the Fed will have leading into the next tightening cycle. |

|

FFTR

0.25-0.50% |

Fed's fully-telegraphed move to raise interest rates sent the markets on a crazy afternoon ride

(18 Mar 2022) Not only did everyone know an interest rate hike was coming at the Fed's March FOMC meeting, the widely-accepted terminal point—the point at which the hikes would probably cease—was somewhere between 2.5% and 2.75%. That is precisely the script Fed Chair Jerome Powell followed as he announced the 25-basis-point hike and hinted at one more for each of the six remaining meetings for 2022. That would be a total of seven hikes this year, bringing the target band of the Federal funds rate between 1.75% and 2.00%. For no rational reason, the Dow, which had been up as much as 500 points on the day, suddenly went negative. Did the "every meeting will be a live meeting" comment spook the markets? That makes little sense. Powell did seem to calm nerves during his press briefing and Q&A session, and the markets began their second major turnaround of the day. He mentioned the need to begin reducing the Fed's balance sheet beginning "at a coming meeting," which was also expected (The prior $120 billion per month Treasury/MBS buying program finally ended a few weeks ago.) On one hand, we are being told that inflation is out of control due to the Fed's slowness to act; on the other hand, we are being told that too many rate hikes will all but guarantee a recession. Fortunately, Powell and the voting members of the Committee will ignore the chatter and do what they think is right. By the end of the day, the markets applauded the day's events, with the Dow finishing the session up 519 points. It still amazes us that certain high-ranking individuals (at the time) thought that Powell was too slow to lower rates a few years back, and that rates should essentially stay at zero for the foreseeable future. With the lower band of the FFR at zero, the Fed balance sheet at a stuffed $9 trillion, and inflation at 7.5%, we believe a rate hike at each meeting this year would be a responsible course of action. Now we are being told by a number of high profile economists that a soft landing of the economy will prove to be near impossible, no matter what the Fed does. We don't buy that theory at all, assuming the Ukraine crisis doesn't mushroom into something much larger. |

|

Yield Curve

47 bps |

The Bank of America analyst who predicted seven rate hikes this year isn't too concerned about the tightening yield curve

(16 Feb 2022) We just explained why investors shouldn't be overly concerned with a series of rate hikes, but what about concern over the flattening yield curve? Many economists are wringing their hands over the tightening spread between the 2-year Treasury and the 10-year Treasury, with some seemingly wired to believe that an inverted curve (the blue line on the chart going below 0.00%) signals a recession is all but guaranteed. Ironically, we turn to someone whose rate hike predictions we don't buy to explain why this is not necessarily the case. There's an old joke—at the expense of economists—which says, "The yield curve has predicted eight out of the last four recessions." Funny. Bank of America's head of global economics, who is calling for seven hikes in 2022 and another four in 2023, made an interesting observation about the tightening curve. He argues that foreign investors are flooding in to buy 10-year US Treasuries because they are faced with zero—or even negative—rates back home. That is a great point. As demand goes up for the longer notes, the law of supply and demand says prices will naturally go up. In Bond World, high demand and higher prices means yields will naturally fall. Picture the teeter-totter rule of bonds. The longer the maturity, the further out on the teeter-totter the bonds sit. On the opposite side of price for any given maturity sits yield. In other words, as prices go up, yields come down, and the longer the duration or maturity, the faster this takes place. Yes, the Fed will raise rates, but they can only affect the short end, sitting nearest the fulcrum on our imaginary piece of playground equipment. This is certainly one strong explanation for the tightening curve. For the record, the B of A analyst, Ethan Harris, also believes that inflation will come down naturally to the 3% range or so in the not-too-distant future as a result of supply constraints easing and the economy getting back to more normal levels. So, we agree with everything he is espousing except for the eleven rate hikes. We are sticking with our prediction of four, 25-basis-point hikes this year, and four more in 2023; this would place the Fed funds rate at a quite accommodative 2%. If that rate freaks the market out, we have bigger concerns about the psyche of investors. |

In a move applauded by the markets, Biden reappoints Powell to lead Fed for four more years

(22 Nov 2021) While we expected President Biden to renominate Jerome Powell as the Fed chief, there were no guarantees. The apparent runner-up in the race was Fed Board Governor Lael Brainard, a favorite by progressives in Congress. To realize just how much Powell is loathed by some on the far left, consider Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren's comments to the Fed Chair earlier this year: "...Over and over, you have acted to make our banking system less safe, and that makes you a dangerous man to head up the Fed, and it's why I will oppose your renomination." Moderate Democrats, however, have backed Powell, as have a majority of Republican senators. While Biden may face some grief from the more fractious wing of his party, he did offer the group an olive branch by nominating the more dovish Lael Brainard for the vice chair position. Furthermore, he will get to fill three more Board seats as three current governors will be stepping down soon. Arguably the third-most-important pick—behind that of Powell and Brainard—will be his selection to fill the role of top bank regulator at the central bank. This will almost assuredly be a candidate looking to put more controls on the financial system. While the senate will undoubtedly approve Powell and Brainard, the regulator role could spark some ugly fights in the senate early next year. The markets clearly liked the renomination of Powell, and investors have come to terms with the fact that the bond buying program will end by the middle of next year followed by a series of rate hikes. We expect inflation to moderate as the supply chain issues get resolved and more Americans re-enter the workforce, so 2022 is shaping up to be a decent year for equities—barring any major unexpected jolts.

(22 Nov 2021) While we expected President Biden to renominate Jerome Powell as the Fed chief, there were no guarantees. The apparent runner-up in the race was Fed Board Governor Lael Brainard, a favorite by progressives in Congress. To realize just how much Powell is loathed by some on the far left, consider Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren's comments to the Fed Chair earlier this year: "...Over and over, you have acted to make our banking system less safe, and that makes you a dangerous man to head up the Fed, and it's why I will oppose your renomination." Moderate Democrats, however, have backed Powell, as have a majority of Republican senators. While Biden may face some grief from the more fractious wing of his party, he did offer the group an olive branch by nominating the more dovish Lael Brainard for the vice chair position. Furthermore, he will get to fill three more Board seats as three current governors will be stepping down soon. Arguably the third-most-important pick—behind that of Powell and Brainard—will be his selection to fill the role of top bank regulator at the central bank. This will almost assuredly be a candidate looking to put more controls on the financial system. While the senate will undoubtedly approve Powell and Brainard, the regulator role could spark some ugly fights in the senate early next year. The markets clearly liked the renomination of Powell, and investors have come to terms with the fact that the bond buying program will end by the middle of next year followed by a series of rate hikes. We expect inflation to moderate as the supply chain issues get resolved and more Americans re-enter the workforce, so 2022 is shaping up to be a decent year for equities—barring any major unexpected jolts.

|

Fed Balance

Sheet $8.556T |

The Fed just announced a refreshing move; even more refreshing was the market's muted reaction to the news

(03 Nov 2021) In June of 2020, we wrote of the Fed's announcement to continue buying $120 billion in bonds ($80 billion in Treasuries and $40 billion in mortgage-backed securities, or MBS) until the economic situation had stabilized to the point at which they could begin tapering those purchases. At the time, the Fed's balance sheet—which is part of our $28.9 trillion national debt—had already mushroomed from $4 trillion to $7 trillion. Today, as the Fed's balance sheet sits at $8.6 trillion, the big moment has arrived: Fed Chair Jerome Powell announced on Wednesday that the purchase program would be reduced by $15 billion ($10B Treasuries, $5B MBS) per month, beginning immediately. At this clip, the program would end entirely by June of 2022. Investors breathlessly awaited the market's reaction. Impressively, neither the stock market nor the bond market did much of anything in response. In fact, the major indexes actually began to strengthen into the close as Powell conducted his press briefing. It is refreshing to see that the move did not cause any type of "taper tantrum," as a similar move did back in 2013. Credit to the Fed for masterfully telegraphing the inevitability of this action. Now, let's see how the market reacts when rates begin to inch up, probably in the second half of next year. It is depressing to look at America's national debt, especially knowing full well that it will ultimately have an enormous negative impact on this country's economy. While the Fed's move won't help reduce that load (at least until the program ends and some of the bonds begin to "fall off" of the balance sheet), it is somewhat comforting to know that it won't grow it at a guaranteed rate of $120 billion per month. Just as every family should be able to rattle off their total debt in an instant, every American should know how much debt their government holds. After all, we are all ultimately responsible for outstanding bill and its ever-accruing interest. |

|

National Debt

$28.4 trillion |

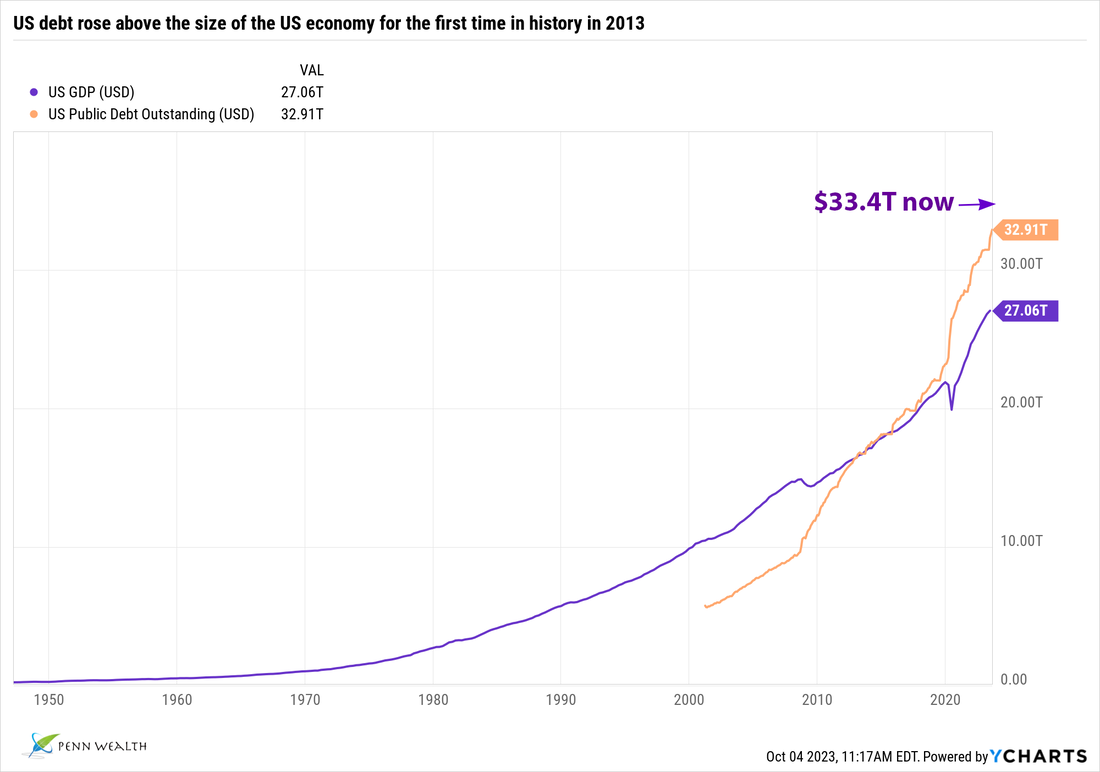

There is quite a bit of disingenuousness going on right now over the topic of raising the debt ceiling

(29 Sep 2021) In its simplest terms, the US debt ceiling provides a limit on how much debt the US government can incur by issuing and selling new bonds. Once that limit is reached, the US Department of Treasury must find other ways to pay its bills—like the $350 billion or so due in interest payments each year to service its debt. Or, as has been the case some 75 other times since 1962, it can simply go to Congress and ask the legislative branch to wave its magic wand and increase or suspend the debt ceiling. How much money are we talking about? Right now, the US has a staggering debt load of $28.5 TRILLION. The debt ceiling level is actually $22 trillion, but it has been on a two-year suspension via Congressional action taken in the summer of 2019. These figures have been mysteriously missing in the current debate over raising the limit. We have heard lofty talk that the "US must honor its obligations," but we haven't heard the $28.5 trillion figure mentioned once. Just how big is that number? Let's put it in perspective. The anything-but-fiscally-responsible European Union mandated that its member-states maintain a debt-to-gdp ratio of 60% or less. In other words, if the GDP of a nation were $1 trillion, it must carry no more than $600 billion in national debt. Seems reasonable, right? As of right now, the US has the largest GDP in the world, at $23 trillion. But, with a debt load of $28.5 trillion, our current debt-to-GDP ratio is 125%—more than double what the EU mandates for its member-states. In fairness, the EU is finding it virtually impossible to enforce that mandate, but also in fairness, shouldn't the level of our own debt at least be part of the discussion? We are on an unsustainable path. There is virtually zero chance that the US debt level will ever come down again, barring a cataclysmic event. In fact, the last time it did go down year-on-year was 1957 under the Eisenhower Administration, when it was reduced from $273 billion to $271 billion. Ah, the glorious '50s. Of course, the US Congress will ultimately raise the debt ceiling once again, as nobody believes we would or should default on our debt payments. But the government cannot continue to spend $1.5 trillion more per year than is brought in via taxation. The pandemic is the most recent excuse for irresponsible fiscal behavior, but trust us, another "emergency" will manifest each subsequent year. This path is unsustainable. The latest scheme, supported by some members of Congress such as Rashida Tlaib of Michigan, is to let the US Treasury mint a $1 trillion platinum coin, and then more as needed, avoiding the pesky legislative branch altogether. The White House has rejected this idea, but proponents have begun the #MintTheCoin movement. The saddest aspect of this warped concept is the fact that the citizens Tlaib purports to represent, the lowest income earners, are the ones hurt the most by the irresponsible level of national debt. We must stop this madness and force the government to live within its means, which means not spending $1 more per year than is brought in. That won't reduce the travesty that is the national debt, but it would at least staunch the hemorrhaging. |

The Fed calmed market fears last week, but its growing balance sheet is concerning

(22 Mar 2021) Fed Chair Jerome Powell said just about everything right at his Q&A following last week's FOMC meeting. The Fed upgraded its US GDP expectations for the year from 4.2% to 6.5%; inflation may well go above 2% in the short-term, but that was OK; and the central bank would continue buying bonds at a clip of $120 billion per month. The markets may have cheered the news, but the rising debt load of the Fed, which is part of the nation's $28 trillion overall debt load, is concerning. Before the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed's balance sheet was below $1 trillion. It more than doubled due to the crisis, then plateaued around $2.8 trillion before mushrooming again in 2013 and 2014. Steady at about $4.5 trillion for several years, it did something few would expect: it began falling—all the way back down to $3.6 trillion in September of 2019. Of course, we know what hit the world six months later, causing the balance sheet to more than double. Just shy of $8 trillion now, we can expect (based on Powell's comments) that it will hit $9 trillion before any talk of tapering. Of major note at the FOMC meeting was the fact that only four members saw rates rising in 2022 and another eight (of the eighteen) saw rates coming off of zero in 2023. That is remarkable, at least until we consider that every tick up in rates makes servicing our $28 trillion national debt all the costlier. At least we are not alone in the boat; governments around the world are awash in debt, with few showing signs of hiking rates. In the meantime, let the party continue. For the first time in a year, the pandemic is not the market's biggest concern—and that is wonderful news. Right now, investors have turned their attention to inflation and Treasury rates creeping up. Our biggest concern right now is none of the above. We see valuations reaching crazy levels on some high-flying tech names which won't turn a profit for years. There will be a tech reckoning at some point this year, which is one reason we have been maneuvering toward a value tilt. Also, portfolios simply got overweighted in growth names due to the run-up. This spring is certainly a good time for a portfolio tune-up.

(22 Mar 2021) Fed Chair Jerome Powell said just about everything right at his Q&A following last week's FOMC meeting. The Fed upgraded its US GDP expectations for the year from 4.2% to 6.5%; inflation may well go above 2% in the short-term, but that was OK; and the central bank would continue buying bonds at a clip of $120 billion per month. The markets may have cheered the news, but the rising debt load of the Fed, which is part of the nation's $28 trillion overall debt load, is concerning. Before the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed's balance sheet was below $1 trillion. It more than doubled due to the crisis, then plateaued around $2.8 trillion before mushrooming again in 2013 and 2014. Steady at about $4.5 trillion for several years, it did something few would expect: it began falling—all the way back down to $3.6 trillion in September of 2019. Of course, we know what hit the world six months later, causing the balance sheet to more than double. Just shy of $8 trillion now, we can expect (based on Powell's comments) that it will hit $9 trillion before any talk of tapering. Of major note at the FOMC meeting was the fact that only four members saw rates rising in 2022 and another eight (of the eighteen) saw rates coming off of zero in 2023. That is remarkable, at least until we consider that every tick up in rates makes servicing our $28 trillion national debt all the costlier. At least we are not alone in the boat; governments around the world are awash in debt, with few showing signs of hiking rates. In the meantime, let the party continue. For the first time in a year, the pandemic is not the market's biggest concern—and that is wonderful news. Right now, investors have turned their attention to inflation and Treasury rates creeping up. Our biggest concern right now is none of the above. We see valuations reaching crazy levels on some high-flying tech names which won't turn a profit for years. There will be a tech reckoning at some point this year, which is one reason we have been maneuvering toward a value tilt. Also, portfolios simply got overweighted in growth names due to the run-up. This spring is certainly a good time for a portfolio tune-up.

|

FFTR

0-0.25% |

Fed's projections show zero interest rates and explosive debt

(15 Jun 2020) Great news if you are going to buy a new home or auto; terrible news if you are living off of the income generated from your investment portfolio. During last week's Federal Open Market Committee meeting and Powell's subsequent news conference, the central bank made it clear that near-zero interest rates will be the norm through 2022. Additionally, the Fed will keep buying bonds, to the tune of $80 billion a month in Treasuries and $40 billion in mortgage-backed securities. Telling us what we already assumed, the Fed projects a 6.5% contraction in the US economy this year. If there was one bright spot in the meeting/commentary it was this: the bank's economic models predict a 5% GDP growth rate in 2021 followed by a 3.5% gain in 2022. Chairman Powell sees a strong bounce-back in economic growth in the second half of this year, assuming no major recurrence of the pandemic this fall. As for the Fed's balance sheet, which it had whittled down to $4 trillion or so, it has now mushroomed back to over $7.2 trillion—and it is growing by roughly $120 billion each month. Putting that in historical perspective, in 2009 the Fed's balance sheet added up to a grand total of $475 billion. |

|

FFTR

1-1.25% |

Fed makes rare "between-meeting" move, and all it did was drive the markets down and sink the 10-year to record lows. (03 Mar 2020) The last time the Federal Reserve made an interest rate cut between FOMC meetings was during the heat of the financial crisis. Today, the Fed shocked the markets by making the equivalent of not one, but two cuts. The 50-basis-point drop moved the Federal funds rate to a channel between 1% and 1.25%. At first, markets seemed to like the action, with the Dow moving from several hundred points down to several hundred points up. That didn't last long. Within a few hours, the Dow was down 800 points and all three major indexes were off around 3%, giving up most of Monday's gains. Not only did the Fed's action not assuage investors' fears, it also drove the 10-year Treasury down to below a 1% yield for the first time in its history. As we write this, it sits at 0.942%. What the markets are looking for now is not more easing, but better news on the coronavirus front. The chronic, minute-by-minute and hour-by-hour hyperbolic coverage is bouncing around in the psyche of investors; until those headlines subside, expect wild trading days with the volatility index, as recorded by the VIX, remaining highly elevated.

|

|

FFTR

1.5%-1.75% |

Fed stands pat in December, and investors like what was implied about 2020. (11 Dec 2019) Ever since that December, 2018 rate hike and the accompanying commentary by Fed Chair Jerome Powell (and that pesky market selloff), our heart rate goes up during each FOMC meeting and—especially—the post meeting press conference. But, a lot like his last meeting, Powell said exactly what the markets wanted to hear. Not only was it a unanimous decision (that doesn't happen often) to leave rates unchanged, Powell implied that the Fed wasn't going to be in a hurry to make a move in 2020. In fact, that scenario is precisely what we are predicting in our 2020 Outlook: no rate cuts, no rate hikes. Powell said he wants to see a "significant and persistent" move in inflation before raising rates. We certainly don't see that happening next year. So, we are left with a range-bound federal funds rate of 1.5% (lower channel) to 1.75% (upper channel). We hate the overused term Goldilocks scenario, but it fits in this case. Also, much to our surprise, Nancy Pelosi is actually going to bring USMCA up for a vote, and it will pass easily in both chambers. Now, if we could just get that elusive "phase 1" trade deal done, 2020 may be off to a very nice start. The election remains the largest unknown in 2020. If Elizabeth Warren is the nominee (we don't see that happening), look for a serious market correction. The impeachment circus means nothing, as investors are expecting the president to be impeached, which will mean precisely nothing after the senate grabs the paperwork and shreds it (20 GOP senators are needed; the Dems may have 3, max).

|

|

FFTR

1.75%-2% |

The Fed made its second rate cut, and the markets were unsure how to react. (19 Sep 2019) It was almost a given going into this week's FOMC meeting: Powell and company would cut rates 25 basis points, to a lower limit target rate of 1.75%. And that is precisely what happened. The somewhat odd initial reaction by the stock market was a selloff. Why? A rate cut is what investors (and the president) were clamoring for, so why throw a fit? Taking it a step further, Powell did a nice job during his post-rate-cut news conference, essentially stating that he still expects economic growth domestically, but that the global economy is certainly slowing. Nothing we didn't already know. To be sure, if Donald Trump were the Fed Chair, we would already have negative rates, following Germany and much of the world down dangerously-uncharted waters, but we believe Powell did the right thing. Perhaps it was the larger number of dissenters (including non-voting members) this time around: five fed members wanted no rate cut, five supported the cut, and seven of the twelve believe there should be one more cut later this year. We believe the seven will get their way—gear up for a 1.5% rate and expect no more. The market's reactionary response is getting a bit silly. What is the point of cutting interest rates other than spurring economic activity? If companies cannot afford to finance new projects with rates where they are now, they probably shouldn't be borrowing at all. We still believe Europe's experiment with negative interest rates and new quantitative easing will end badly. And that is what investors are currently missing.

|

|

FFTR

2.00-2.25% |

The Fed lowers rates for the first time in eleven years. (31 Jul 2019) The Fed just did something it hasn't done since December of 2008: it lowered rates. The bottom line of the Fed funds target rate now sits at 2%, something that might appear remarkable were it not for the $14 trillion worth of bonds and notes around the world carrying negative yields. Despite the 2% target, investors will continue to clamor for more cuts in 2019, which may lead to some ugly days in the market if they don't get what they want.

|

|

FFTR

2.25-2.5% |

The Fed held steady with their benchmark rate: the markets cheered and the president jeered. (20 Jun 2019) The Fed Funds Target Rate is currently in a band between 2.25% and 2.5%. By all historical standards, that is ultra-low. Furthermore, the unemployment rate in the US sits at 3.6%—full employment by the Fed's own definition. Why, then, would the central bank even consider lowering rates? The argument, made by the president and others, is that inflation continues to be frustratingly low—well below the Fed's 2% target. Also, there are signs of slowing productivity in the country, as measured by GDP. As for inflation, we have posited our rationale for the low rate many times in the past. It has to do with technological advancements keeping a clamp on prices. And we have time to wait and see how the GDP numbers look going forward. In other words, why lower rates? Markets rallied after Wednesday's decision not because the Fed stood pat, but because they left the door wide open for rate cuts as soon as the July meeting. What we find most interesting in this story is the leaked report that President Trump either wants to fire Fed Chief Powell (he cannot) or demote him (he probably cannot). Did Powell screw up with the December rate hike last year? Perhaps. But he has actually done a very good job at balancing economic needs with stock market wants. And that is no easy act. If the president tries to demote Jerome Powell, the markets will not rally (as Jim Cramer predicted). It would amount to the creation of a crisis out of thin air. From a logistical standpoint, it would be fascinating to watch. Hopefully, the conflict will be relegated to our imagination and the columns of pot-stirring journalists.

|

Unlike Powell's disastrous Q4 remarks, Wall Street cheered his new attitude. (30 Jan 2019) Every news conference, every Q&A session, every guest appearance Fed Chief Jerome Powell performed at in the fourth quarter was a disaster. He was, in good measure, the reason we had such an ugly quarter. Somebody or something got to him, as he gave the performance of a lifetime on Wednesday. We didn't need Nielsen for the feedback, we had the markets: by the end of the day the Dow was up 435, the S&P was up 41, and the NASDAQ spiked 155. Powell used the terms "patient" or "patience" at least eight times that we counted. It was brilliant. Instead of the reduction of the $4 trillion Fed balance sheet being on "auto pilot" (Powell-speak in 2018), it was "we will wait and see." We couldn't have written a better performance. One very interesting note on the $4 trillion balance sheet, that the Fed had been reducing at a clip of $500 billion per month: it now appears as if it may get down to $3.5 trillion and the QT (quantitative tightening) will actually stop. That is an enormous shift in policy from the central bank. As for rate hikes, we stick by our one (max) for the year; probably coming in June or even later.

|

FBS

$4.09T |

Powell's second mistake at the FOMC news conference. (20 Dec 2018) In addition to the harshly-negative reaction the markets had to Powell's "more hikes to come" comments following the ninth rate hike in three years, there was something else he alluded to that angered and spooked investors. Of the Fed's four major tools for shaping monetary policy, two are at the forefront right now: moving the federal funds rate (which it did on Wednesday), and controlling the size of its balance sheet through open market operations. As if the specter of two more rate hikes in 2019 wasn't bad enough, Powell made it clear that the systematic unwinding of the $4 trillion balance sheet (already reduced from $4.5 trillion) would continue like clockwork. The Fed is currently allowing roughly $50 billion per month to run off the balance sheet by letting government debt instruments simply mature, and not issuing new debt to replace it. On its face, that sounds like good fiscal policy, as it reduces the overall level of government debt. But investors see a lot of troubling factors on the horizon, and they expected Powell to tip his hat to this and hint that the unwinding, or quantitative tightening (QT, as opposed to QE) might be put on pause or, at least, slowed. They were sadly disappointed. Forget what Powell says, signs that the Fed "gets it" will come in the form a reduced runoff of the balance sheet. I use the Federal Reserve Board website to look at the data. I have placed a link to the site at the top of this page. Take a look!

|

|

FFTR

2.25-2.5% |

Another rate hike: fed funds rate now at 2.5%, long-run funds rate lowered to 2.8%. (19 Dec 2018) It was one of the most heated periods of debate leading up to any FOMC meeting in recent memory. And the camps were about evenly split between "the Fed must raise rates," and "the Fed will lose credibility if it raises rates again." Going into the 1pm CST decision, the Dow was up nearly 300 points; within seconds after the announcement, it was flat. What bothered the markets so much wasn't the highly-anticipated ninth rate hike since October of 2015, it was the fact that the language wasn't quite dovish enough. If Fed Chair Powell hadn't said that more rate hikes will probably be needed in 2019, markets probably would have maintained their gains on the day. Instead, he hinted at two more hikes in 2019, and potentially even one for 2020. The "long-run funds rate," which had been at 3%, was lowered to 2.8%. That would indicate one to two more hikes next year—not what investors wanted to hear. Despite the loss of most of the day's gains after the Fed announcement, markets can digest this one (mainly because stocks have been so deflated this quarter already). However, if the Fed obstinately raises rates in 2019, expect an immediate tantrum in the markets. One more X-factor to be concerned with next year.

|

|

FFTR

2-2.25% |

Fed sees bright economic future, raises rates once again. (26 Sep 2018) The Federal Reserve is bullish on the growth within the US economy, and they do not want that growth to lead to runaway inflation (even though there are really no signs of this happening). With that as the backdrop, the FOMC raised the Fed Funds Rate 25 basis points on Wednesday, to 2.25%. But they didn't stop there. After raising their economic outlook for the country, members also projected one more hike this year and three in calendar year 2019. In the long run, however, they see a stable Fed Funds Rate at 3%, meaning a few potential rate cuts after 2020. While we don't necessarily believe they will deliver on the four-more-hikes prediction, what would this do to the 30-year mortgage rate? Although certainly still below generational highs, the average mortgage would probably cost buyers 6% to 6.25%. With existing-home sales already slowing, that could certainly impact homebuilders. However, we still see that in the manageable range—not high enough to hurt the economy. From an investment standpoint, we should continue to see improved yields, which will provide welcome relief to those seeking more income but less risk.

|

Powell gives masterful performance on Capitol Hill, avoids efforts to drag him into politics. (17 Jul 2018) The blowhard politicians sitting atop their Mount Olympus grandstand did everything but tell Fed Chairman Jerome Powell exactly what to say. With their typical "well everyone knows" and "you have to admit" comments, they pushed and prodded him to enter the political fray with his economic outlook, but he didn't bite. What he did say was that the strong US economy and stable inflation should keep the Fed on its current track of regular rate hikes. If the politicians didn't get Powell to say what they wanted to hear, their friends in the press took over, writing things that Powell simply did not say. I watched the entire grilling, and I read what was written in the Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg. There were discrepancies. As to why, we will leave that up to readers to decide motive. One thing is certain, Powell has a clearer and more direct speaking style than any Fed Chair we recall, and that is going back to Paul Volcker in the '70s. Look for at least one more rate hike in 2018, with an outside possibility of another (which would bring the total this year to either three or four).

All of a sudden, inflation is at the Fed's target. (29 Jun 2018) One of the key metrics used by the Federal Reserve with respect to monetary policy is the rate of inflation, ex-food and energy costs (these are too volatile to get an accurate reading of the overall trend). For years, the Fed has held an official target rate for inflation at 2%; and for (six) years, it has been below that level. No longer. The aggregate basket of goods used to gauge inflation rose 2% between May of 2017 and last month—the first time that mark has been reached since 2012. If there is anything the Fed is more freakish about than a recession, it is runaway inflation. Members of the Board of Governors often make the claim that once inflation begins to get out of hand, it is extremely hard to tame. What does this mean? An almost certain continued and steady series of 25 basis point rate hikes. Great news for bond hunters; not-so-great news for anyone waiting to buy that new home. Don't expect to see rates tickling zero again for a long, long time. On the flip-side, Germany's economy remains so anemic that the yield on the 10-year bund recently hit 0.305%.

Yield spread shrinks to narrowest gap in 11 years—so what? (14 Jun 2018) As of this writing, the 2-year Treasury is yielding 2.570%, and the 10-year Treasury is yielding 2.937%. The difference in yields is 36.7 basis points—the narrowest gap in nearly a dozen years. Who cares? Banks do, for sure. The spread between what they charge clients to borrow and what they get paid for the assets they hold correlates directly to the Treasury bond spread. When it narrows, they make less. So, is a smaller spread bad? Not necessarily. Yes, an inverted yield curve—when short-term rates are higher than longer-term rates—almost always signals that a recession is coming. But, the rates getting a bit closer together is a typical reaction to a Fed tightening cycle, which we are in right now. No need to worry about the flattening yield curve, but it is a good time to review your financial sector holdings.

|

FFTR

1.75-2% |

As expected, Fed Funds Rate is hiked to 2%. (13 Jun 2018) The Federal Reserve, as highly anticipated, raised interest rates by 25 basis points on Wednesday, to an upper range of 2%. This represents the fourth rate hike, or 100 basis points in aggregate, within the past year. We anticipate one more hike this year, and as many as three in 2019 before we settle into "normalcy." Expectations for US economic growth have risen to 2.8%. If we get four more hikes over the next year, that would put the Fed Funds Rate at 3%, which the central bank would consider to be in the normal range. During Fed Chair Powell's question and answer period, he stated that a 3% growth rate in the US would not be outside the realm of possibility, or even that surprising.

|

Fed holds rates steady at 1.75% but still indicates more hikes to come

(02 May 2018) As expected, the Federal Reserve did not raise the benchmark rate to 2% at Wednesday's meeting, but we should still look for two more rate hikes this year—barring any disaster between now and the June meeting. Inflation, over any other metric, seems to be what members are keeping their eyes on, as once it gets out of control it becomes very hard to contain. And that metric just hit the Fed's 2% target in March. There is an argument as to whether or not the "Amazon effect" is keeping inflation muted. The theory behind that thinking is that Amazon has created such a competitive environment in the retail marketplace other players must keep their prices low to hold their ground. That is an untested theory, and one we don't really buy. The US economy is enormous, even by Amazon's standards. The real question is how the stock market will react to a 2% benchmark rate when it comes this summer.

(02 May 2018) As expected, the Federal Reserve did not raise the benchmark rate to 2% at Wednesday's meeting, but we should still look for two more rate hikes this year—barring any disaster between now and the June meeting. Inflation, over any other metric, seems to be what members are keeping their eyes on, as once it gets out of control it becomes very hard to contain. And that metric just hit the Fed's 2% target in March. There is an argument as to whether or not the "Amazon effect" is keeping inflation muted. The theory behind that thinking is that Amazon has created such a competitive environment in the retail marketplace other players must keep their prices low to hold their ground. That is an untested theory, and one we don't really buy. The US economy is enormous, even by Amazon's standards. The real question is how the stock market will react to a 2% benchmark rate when it comes this summer.

|

FFTR

1.5-1.75% |

Market cheers Fed rate decision and rationale, Fed Funds Rate goes to 1.75%

(21 Mar 2018) We knew there weren't going to be four rate hikes this year, but the talking heads of the financial media had repeated it so many times investors bought in. That is why, after the Fed raised rates and remained on a path for three 2018 hikes, the markets went from relatively flat to up 200 points on the Dow. It really was a positive meeting: we got the expected rate hike everyone knew was coming; the Fed was very optimistic on the economy; inflation remained muted; and the three rate hike scenario was buttressed. There was an interesting takeaway for next year—comments were made about the potential need to be more aggressive in 2019 to keep inflation at bay. As for the Fed Funds Rate, it now goes to a benchmark of 1.75%, and the 10-year Treasury rose above 2.9% following the move. |

The 10-year Treasury is becoming disconcertingly intertwined with market volatility

(22 Feb 2018) Early in Thursday's trading session, the Dow was up over 300 points. The reason? The 10-year Treasury yield pulled back from its recent four-year high of 2.92%. The day prior, when Fed minutes were released showing the central bank's belief that the economy is doing great, the 10-year yield spiked, immediately sending the Dow from plus 150 points or so to minus 166 points at the close. The value of the 10-year (which drops as the yield rises) is becoming a disturbingly accurate proxy for the stock market. That could be ominous, considering we are probably looking at three rate hikes this year and three in 2019. Will we have to go through this market tantrum with each Fed meeting? Perhaps. Right now, the Fed Funds Rate is sitting at 1.5%. Three more 25-basis-point hikes, and it will be at 2.25%. That will force the 10-year Treasury yield up above 3%. After three more hikes in 2019, it will probably be sitting near 3.5%. We consider that yield to be the flash-point for real potential carnage in the market. Hopefully, inflation will be still be deemed tame enough for Powell's Fed to stop there. Between now and then, look for a spike in volatility around each FOMC meeting—like the one on 20/21 March, when rates will likely rise once again. The bright side? We should finally be able to start picking up some better-yielding corporates.

(22 Feb 2018) Early in Thursday's trading session, the Dow was up over 300 points. The reason? The 10-year Treasury yield pulled back from its recent four-year high of 2.92%. The day prior, when Fed minutes were released showing the central bank's belief that the economy is doing great, the 10-year yield spiked, immediately sending the Dow from plus 150 points or so to minus 166 points at the close. The value of the 10-year (which drops as the yield rises) is becoming a disturbingly accurate proxy for the stock market. That could be ominous, considering we are probably looking at three rate hikes this year and three in 2019. Will we have to go through this market tantrum with each Fed meeting? Perhaps. Right now, the Fed Funds Rate is sitting at 1.5%. Three more 25-basis-point hikes, and it will be at 2.25%. That will force the 10-year Treasury yield up above 3%. After three more hikes in 2019, it will probably be sitting near 3.5%. We consider that yield to be the flash-point for real potential carnage in the market. Hopefully, inflation will be still be deemed tame enough for Powell's Fed to stop there. Between now and then, look for a spike in volatility around each FOMC meeting—like the one on 20/21 March, when rates will likely rise once again. The bright side? We should finally be able to start picking up some better-yielding corporates.

|

Fed Chair

|

Jerome Powell overwhelmingly confirmed to become the 16th chairman of the Federal Reserve

(24 Jan 2018) By a vote of 85-12 (seriously, what was going through the mind of a senator who voted "no"?), Jerome "Jay" Powell was confirmed by the senate to head the central bank of the US. Though he won't physically take the helm until Janet Yellen's term expires on 03 Feb, he already has a lot to prepare for. The Fed is in the nascent stages of unwinding its record $4.5 trillion balance sheet (which is a line item on the national debt), and momentum for interest rate hikes is gaining steam. For the record, we believe there will be three rate hikes in 2018, bringing the benchmark Fed Funds Rate to 2.25%. The catalyst for these hikes will be an unexpectedly high GDP and fear of inflation. We also believe Powell is the right person for the job. |

|

Fed Funds

|

Fed raises interest rates another 25 basis points to benchmark of 1.5%

(13 Dec 2017) The Federal Reserve raised interest rates for the third time this year, to a benchmark of 1.5%, at their December meeting. The central bank also signaled more hikes in 2018 as growth is expected to ramp up. GDP projections for the coming year were raised from 2.1% to 2.5%, and the unemployment forecast was lowered to 3.9%. As for the number of rate hikes in 2018, we can probably expect three, which would raise the benchmark Fed Funds rate to the 2.25% range. The Dow, which was up 100 points at the time of the announcement, shot up to plus-116 points immediately following the highly-anticipated announcement. |

|

Fed

|

President Trump nominates Jerome "Jay" Powell as next Chairman of the Federal Reserve

(02 Nov 2017) President Donald Trump has nominated Jay Powell, currently a member of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors (appointed by Barrack Obama in 2012 as part of a "one Republican and one Democrat" deal), to be the next Fed chief, replacing Janet Yellen. The markets cheered the news. There are many things we love about Powell as the next chairman of the Fed; here are two: he has real world business experience, and he is not an economist. Fantastic choice. |

|

Inflation

|

A unique and historical dynamic is keeping inflation below the Fed's target

(12 Oct 2017) The Federal Reserve often cites its target 2% inflation rate as a major metric for deciding when to raise interest rates. While a December rate hike is all but assured, the Fed is having trouble explaining why inflation is so muted. After all, with a 4.2% national unemployment rate and rising wages, the key catalysts for inflation seem to be in place. What they may be missing, however, is the disruptive impact technology is having on keeping prices low. The grocers, for example, would love to raise rates, but Amazon won't let them. Clothing retailers certainly need the cash, but they are doing everything they can to attract shoppers. OPEC would love to see oil back at $100 per barrel, but US shale producers and a big alternative energy push is keeping the price around $50. All this is great news for consumers; not so much the Fed's numbers crunchers. |

Is the Fed really going to start reducing its $4.5 trillion balance sheet?

(06 Apr 2017) While everyone is focused on the next Fed rate hike, we need to remember that they have two other tricks in their magic kit: the ability to change the reserve requirements of banks, and the buying or selling of US government securities to adjust the amount of money floating around in the marketplace. The latter takes place via a mechanism known as open market operations, or OMO.

After shooting all its ammo on method number one by lowering rates to zero, the Fed began buying trillions of dollars worth of government bonds, mostly during those three nightmarish "quantitative easing" programs. Yes, they become both the issuer and the open-market buyer! This flooded the market with excess capital, having the same effect as lowering interest rates. The trick is to do this in such a manner as to not trigger runaway inflation (due to all of the new money floating around). In theory, the economy is in such bad shape when rates are going lower that inflation is held in check.

Now, after its seven-year buying spree (paid for by you, by the way), the Central Bank of the US has a whopping $4.5 trillion on its balance sheet. Roughly $2.5 trillion of this amount is in Treasuries, and most of the rest consists of mortgage-backed securities. Keep in mind that this $4.5 trillion is part of our national debt, so if the Fed would simply "pay off" these obligations, it would reduce our national debt to about $15.5 trillion.

While no one really expects the Fed to "unwind" the balance sheet altogether, comments made on Wednesday (which drove the market down 150 points or so) do show that they are interested in reducing their bond holdings beginning this year, rather than in 2018. The economy looks strong enough to start this unwinding process, but there is one little fact that has us questioning the Fed's commitment. All of those fixed-income securities on their balance sheet have been paying interest. Essentially, the government has been paying itself. All well and good, but do you think they used the income generated to pay down that balance sheet? Nope. They have been reinvesting the interest payments and allowing the bonds to rollover at maturity! Not a good sign.

Keep an eye on that $4.5 trillion figure to see just how fiscally responsible the Fed has become (after all, Lew is gone at Treasury and Helicopter Ben is not the Chair any longer), and certainly continue to watch what happens to the national debt, which is ever-so-slightly below the $20 trillion mark at the time of this writing. (See usdebtclock.org.)

(Reprinted from the Penn Wealth Report, Vol. 5, Issue 2)

(06 Apr 2017) While everyone is focused on the next Fed rate hike, we need to remember that they have two other tricks in their magic kit: the ability to change the reserve requirements of banks, and the buying or selling of US government securities to adjust the amount of money floating around in the marketplace. The latter takes place via a mechanism known as open market operations, or OMO.

After shooting all its ammo on method number one by lowering rates to zero, the Fed began buying trillions of dollars worth of government bonds, mostly during those three nightmarish "quantitative easing" programs. Yes, they become both the issuer and the open-market buyer! This flooded the market with excess capital, having the same effect as lowering interest rates. The trick is to do this in such a manner as to not trigger runaway inflation (due to all of the new money floating around). In theory, the economy is in such bad shape when rates are going lower that inflation is held in check.

Now, after its seven-year buying spree (paid for by you, by the way), the Central Bank of the US has a whopping $4.5 trillion on its balance sheet. Roughly $2.5 trillion of this amount is in Treasuries, and most of the rest consists of mortgage-backed securities. Keep in mind that this $4.5 trillion is part of our national debt, so if the Fed would simply "pay off" these obligations, it would reduce our national debt to about $15.5 trillion.

While no one really expects the Fed to "unwind" the balance sheet altogether, comments made on Wednesday (which drove the market down 150 points or so) do show that they are interested in reducing their bond holdings beginning this year, rather than in 2018. The economy looks strong enough to start this unwinding process, but there is one little fact that has us questioning the Fed's commitment. All of those fixed-income securities on their balance sheet have been paying interest. Essentially, the government has been paying itself. All well and good, but do you think they used the income generated to pay down that balance sheet? Nope. They have been reinvesting the interest payments and allowing the bonds to rollover at maturity! Not a good sign.

Keep an eye on that $4.5 trillion figure to see just how fiscally responsible the Fed has become (after all, Lew is gone at Treasury and Helicopter Ben is not the Chair any longer), and certainly continue to watch what happens to the national debt, which is ever-so-slightly below the $20 trillion mark at the time of this writing. (See usdebtclock.org.)

(Reprinted from the Penn Wealth Report, Vol. 5, Issue 2)

(15 Mar 2017) As predicted, Fed raises rates 25 basis points. As the positive economic reports continued to flow in this year, it became clear that the Fed would raise rates at its March meeting. That is exactly what happened, as Yellen and company pulled the trigger on another 25 basis point hike—the third in just over two years. In a very good sign of economic confidence, the markets not only didn't react negatively to this hike, there was actually a triple-digit rally on the Dow into the close. This was due, in good measure, to the positive comments Yellen made in the news conference after the event, in which she signaled a relatively good relationship between the Fed and the Trump administration, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin in particular.

(02 Mar 2017) Penn predicting a 25 basis point rate hike at March meeting. We went nine years between interest rate hikes before Yellen pulled the trigger in December of 2015. The Fed did it one more time this past December. While everyone was shocked at the time that more rate hikes didn't occur, we had our eyes on what the Fed is really looking at—the rate of inflation. Once inflation begins to spread, it is almost impossible to contain without something very ugly creeping in first. The FOMC puts the "Goldilocks" inflation target at 2%. Right now, that metric is sitting at about 2.5%. This fact, we believe, will dictate a rate hike at the Fed's March meeting. We also believe there will be one to two more hikes in 2017.

After the weakest recovery in the modern era, the economy is finally picking up steam and, despite the recent market run-up, we believe investors have baked in these hikes. While retirees on a fixed income have been waiting a long time for these hikes, realtors and homebuilders sure would like them to stay low a bit longer. At least they can use this as a club to knock wavering home buyers off the fence.

After the weakest recovery in the modern era, the economy is finally picking up steam and, despite the recent market run-up, we believe investors have baked in these hikes. While retirees on a fixed income have been waiting a long time for these hikes, realtors and homebuilders sure would like them to stay low a bit longer. At least they can use this as a club to knock wavering home buyers off the fence.

(15 Feb 2017) The US economy is suddenly growing again, and that will force the Fed's hand. Retail sales, ex-autos, spiked 0.8% from December to January. Factory output rose 0.2% from December to January. CPI, the best measure of inflation, rose 2.5% in January, year-over-year. All of these economic metrics are working in concert with one another to push the Fed forward with more rate hikes—the next possibly coming at the March meeting. And, indeed, rate hikes need to happen. That 2.5% inflation rate is not exactly equivalent to Germany in the 1920s, but history has proven that unchecked inflation can spread like lit kindling in a dry forest. The economy is heating up, and we expect that to continue. That calls for two to three rate hikes this year.

(Left: In 1923, virtually overnight, it took 200 billion marks to buy 1 US dollar)

(Left: In 1923, virtually overnight, it took 200 billion marks to buy 1 US dollar)

(15 Dec 2016) Dollar hits 14-year high against euro. After the Fed raised rates for the second time in over a decade, the US dollar surged against the euro to its strongest point in 14 years. Not too long ago it took $1.60 to buy €1. Now it takes just $1.04, and parity is coming soon. A 60% strengthening is huge; sure, it makes US goods more expensive, but it also signals economic strength. i.e. we are not flooding our economy with currency in an attempt to stimulate. Another good effect: a stronger dollar causes capital to leave China, destabilizing the yuan.

(14 Dec 2016) Fed hikes rate for the first time since last December. Janet Yellen's Fed raised rates 1/4 of a point, to a range of 0.5-0.75—the first rate hike since last December and only the second rate hike in ten years. More importantly (everyone expected this hike), the agency signalled more aggressive tightening next year; we may see, perhaps, two or three rate hikes in 2017. There were no dissents to the decision.

The Fed Finally Pulled the Trigger

(11 Jan 16) In Volume 4, Issue 2 of the Journal, we will look at what the first interest rate hike in nearly a decade will mean for your investments…your loans…your income…and the American economy. Don’t miss it.

(OK, got it. Take me back to the Penn Wealth Hub!)

What Was Bretton Woods?

We recently mentioned that the two organizations borne out of the Bretton Woods Conference have strongly requested that Fed Chair Janet Yellen hold off on raising interest rates this year. But what was this conference all about?

Even though World War II was still raging, under the auspices of the United Nations all 44 Allied countries in the war effort met at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire in July of 1944 to discuss the economic rebuilding of the post-war world. There were three major outcomes of the Bretton Woods meeting; two of which survive today.

The first outcome was the establishment of the International Monetary Fund, or IMF, to promote international financial stability and monetary cooperation. A second organization, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, was created to speed up post-war reconstruction and foster political stability. The IBRD still exists today as the World Bank.

The third outcome of Bretton Woods was an attempt to stabilize currency exchange rates by each nation pegging its currency to its store of gold (the Gold Standard). Sadly (to many), this system was abandoned by President Nixon on August 15, 1971.

Both the World Bank and the IMF are telling Yellen to Hold Off on Rate Hikes

(09 Sep 15) First it was the International Monetary Fund, or IMF; now it is the World Bank. On Wednesday, the chief economist of the institution created by the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944 warned Fed Chairman Janet Yellen that an interest rate hike in 2015 would be disastrous for emerging market countries. Kaushik Basu also pointed to the Chinese and general global slowdown as a clear sign that the US has no business raising rates right now.

The IMF also “expects the US to do the right thing” and wait until well into 2016 to think about raising rates. IMF Chief Christine Lagarde added the US economy to the mix, saying that her expectations for the country had been dampened with the first quarter GDP contraction.

Janet Yellen is not Ben Bernanke, however, and is probably putting little stock in this Euro-centric advice. Rather, she is basing her rate decision on the Fed’s gauge of the overall health of the US economy, which she has deemed to be relatively strong.

While the major US indexes (and the Europeans, and the Russians, and the emerging markets) will probably throw a short-term fit the day that the first interest rate hike in nine years is announced, we believe the tantrum will be short-lived. Yellen has made it clear that it needs to happen soon, but that we can expect a very slow, methodical process after the first rate hike.

For those looking to buy a new house or refinance an existing one, we expect interest rates to remain ultra-low through 2016 and into 2017.

(OK, got it. Take me back to the Penn Wealth Hub!)

Cowardly (or Insidious) Fed Refuses to Stop the Presses

(18 Sep 13) In a move that caught most of us off guard, even those of us who have little to no respect for Bernanke, the Fed has refused to begin tapering its program of flooding the economy with $85 billion per month in a bond buying scheme. With only one courageous dissenter, Kansas City Fed President Esther George, Federal Reserve officials said they wanted to see more strength in the economy before they stop applying leaches to the anemic patient (our words).

The stock market, like a three-year-old in a new candy shop, reacted with glee to the news. We wonder where the AARP commercials are? The political organization which claims to be a beacon of light for retirees sure seems to be quiet on the devastating effect of ultra-low interest rates on its members.

As much as we anticipate Bernanke leaving, it appears that his cookie-cutter replacement will be former San Fran Fed President Janet Yellen. In fact, Wednesday's move to keep the dollar-destroying policy in place may well be a nod to Yellen. It would be an awkward position to put a dove in--begin a tapering program right before another mega-government Fed chair takes her seat.

Bernanke said that the jobless rate remains too high. Wow, what insight. Perhaps the chairman should talk to his fiscal cohorts who have been tying the hands of employers in this country with onerous regulations, including the new, 906 page, Affordable Care Act. The markets may be happy today, but lets see the reaction when the government shuts down due to our inability to pare a $3.6 trillion annual budget--despite the fact that the government will take in $1.16 trillion LESS than that over twelve months. Throw another trillion on the fire, we can tackle this tough problem next year. This is not the American courage I recall growing up around. Esther George, however, would be welcome at the Liberty Tree Tavern.

Whether the Markets Like it or Not, it is Time for the Fed to Ease Up

(10 Sep 13) Like a drug dealer selling crack cocaine, Ben Bernanke's Federal Reserve Bank has been shoving $85 billion a month down our throats through his bond buying program. Mission accomplished, Ben--the victim is hooked. So now, the patient realizes he has an addiction and needs to seek help. As would be expected, his willpower is low due to the steady diet of the feel-good narcotic, and irrational irritability ensues with a mere mention of the remedy.

Talk about a manic-depressive market. When good economic news hits, investors become scared that the Fed is about to start tapering its reckless bond buyback program and the Dow drops triple digits. Bad economic reports, however, bring a sigh of relief that the Fed will stand pat, and the markets rally. Good news is bad news and bad news is good news. One might wonder exactly when the "Romper Room" cast took over in Washington, but that would be an unfair comparison--the children's show we grew up with would actually inject moral lessons into their shows.

Case in point: Friday's lousy jobs report. An increase of 169,000 non-farm payrolls fell well short of estimates, yet the government touted a drop in the unemployment rate to 7.3%. Yes, technically that is correct. However, we might want to consider that the participation rate--the percentage of the labor force which is either employed or seeking employment--fell to 63%. The rate has not been that low since the Bee Gees topped the charts with their Saturday Night Fever soundtrack. Following the Friday jobs report, the Dow ended the day flat and up 113 points on the week.

So why are investors so intimidated by the specter of the Fed turning down the spigot? One big fear is that more risk-averse investors (like retirees who rely on their investment income) will flood out of the riskier equities market and back into their safe bonds once rates start to rise (and rates will rise as the Fed tapers). In addition to money leaving equities, there is also concern that the ensuing interest rate increases will dampen economic activity. After all, retirees may want higher rates, but builders sure don't.

This is not to minimize the risks. They are out there. But the U.S. economy, half a decade after the financial crisis, can withstand a more responsible monetary policy. Perhaps we can even enjoy a short respite before realizing that we have a $17 trillion national debt that will take decades to pay off. Enjoy the speaking tour, Ben.

Wall Street Knows What it Wants, but Does it Know What it Needs?

(30 Aug 13) There has been endless speculation about who will--and who should--replace Ben Bernanke as chairman of the Federal Reserve. Opinions on who the new Fed chief should be are as widely dispersed as the view of the job Bernanke did in his role. From our vantage point, here is what we see: Mr. "Student of the Great Depression," as Bernanke likes to see himself, inherited an $8 trillion national debt when he took the office in February of 2006. Just over seven years later, the national debt has doubled, and it will easily reach $17 trillion before he leaves town (no doubt headed for academia).

For all of the talk of saving us from the brink, there really is no evidence that this unprecedented and never-before-seen level of government spending saved us from anything. In fact, we would argue that the greatest threat America now faces is being able to service its debt load as interest rates rise. With interest rates hovering near zero, a whopping 7% of all the money that government takes from taxpayers now goes to simply servicing (paying interest on) the national debt. When rates double or triple, the interest rate on our national credit card will double or triple. What will that do to all of the precious services the government must now provide? For the past month or so the talk has centered around "tapering," or slowly weening the economy off of the $85 billion PER MONTH government spending spree. Bernanke wants to leave a legacy and begin the tapering before he leaves office early in 2014. Trust us, Ben, your legacy is already set in stone. Just ask a retiree, who has seen their stream of income from bonds and CDs wither down to nothing.

So we turn our attention to who will replace "Helicopter Ben." Wall Street's biggest fear is that former treasury secretary, Harvard president, and Clinton bud Larry Summers will be offered the job. Recently, a group of far left leaning U.S. senators sent a letter to President Obama bashing Summers and demanding that he put former president of the federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Janet Yellen, in the spot. We must ask ourselves why these senators fear Summers so much.

Perhaps for Di Fi (Dianne Feinstein, senator from California), it was Summers' misconstrued comments at Harvard, in which he told a packed audience that more focus should be placed on assuring women are qualified for elite science and engineering positions by assuring they master mathematics. Scandalous! For fat Wall Street cats like Lloyd Blankfein of Goldman Sachs, the answer is a lot more basic. They do not want the government spigot turned off. Summers is a fiscal hawk, and has a much wider apparent grasp of the big economic picture than does Bernanke--who Yellen would likely emulate. Summers understands that the national debt actually is a really big deal, and that it can ultimately crush the U.S. economy.

One of the worst things about Summers (in the eyes of the milquetoasts), is his combative and gruff personality. Unlike the mild mannered and thoughtful Bernanke, who would often stroke his little professor's beard as he addressed congress, Summers might actually shake things up a bit. For the Washington elite and the anointed money brokers of New York, any threat to the status quo is a direct threat to their good ole' boy system. It is encouraging to hear that Larry Summers now has the pole position in the race for the top Fed spot. The markets may throw a fit when the news is announced, but the fireworks should be fun to watch. Who knows, the national debt of the United States might even drop--something that hasn't happened since Ike was in the White House.

Meet the new boss; same as the old boss

(29 Aug 13) While it is true that we had a good time making fun of former U.S. Treasury Secretary (and tax cheat) Timmy Geithner, there was nothing enjoyable in watching him decimate the value of the U.S. dollar by running his printing presses 24/7. We were happy to hear of his eminent departure to join a university, hiding safely behind the ivory pillars which protect the tenured, erudite elitists. At least we wouldn't have to see that goofy head on TV anymore. Our joy was short lived.

One of the reasons given for Tuesday's big slide in the stock market was talk of a Syrian strike. That was only one of the big stories that morning. By the time that news hit, Secretary Lew had already thrown down the gauntlet to a returning congress, promising an ugly political battle this fall. His comments on CNBC that the president would not negotiate, and that "congress needs to come back and do their job" (which can be read as "shut up and give us the tax increases we want and don't ask for responsible spending constraint") led to a palpable angst among investors and helped fuel the big sell-off.

Lew, representing the administration's viewpoint, has taken a calculated but dangerous risk in playing hardball so early in his tenure. He is betting that the American people will see a potential government shutdown as a one-sided affair, giving all of the blame to Republicans ahead of the crucial 2014 mid-terms. This may well be true, and House Speaker Boehner is clearly concerned that his party will face retribution at the ballot box. However, with a $17 TRILLION national debt, which equates to a $53,000 debt placed on every citizen in the United States (seewww.usdebtclock.org), we are nearing a point in the fulcrum where the sentiment scale will begin to tip.

American families understand that they cannot spend more money than they bring in each year, and they are beginning, en masse, to question why they are expected to live by one set of rules while the government lives by another. It is hard to fathom what one trillion dollars of over-spending per year looks like, but Joe or Jane Citizen knows what a taxpayer-funded, IRS-produced Star Trek video looks like. And they know it's not right for a public worker to use his or her Government-issued American Express card at a casino. And they are now seeing these examples played out on the nightly news.

The shift against support for the Vietnam War came about as Walter Cronkite and his peers began inundating viewers with scenes of body bags returning to the United States. As we see more and more images of government employees yucking it up in Vegas ballrooms on team building trips, the tide will continue to turn. Secretary Lew may lose that Cheshire cat grin when he realizes the waves are headed his way.